In response to Donald Trump’s tariffs on Canadian goods, Ontario Premier Doug Ford is threatening to place a tax on electricity exports to the United States, stating, “We’re reviewing the cost of electricity we’re sending down there. And if he puts tariffs on anything in Canada or Ontario, they’re getting a tariff on their electricity.” He’s gone as far as to say that he “will do anything — including cutting off their energy — with a smile on my face."

Cutting off energy exports has obvious symbolic value. Canadians are ready to engage in aggressive tit-for-tat strategies, especially given the saber-rattling over sovereignty. However, for Ontario, taxing electricity exports is a much better solution than banning energy exports.

Taxing electricity exports is likely to make Ontario better off. A 25% export levy leads to a net gain to Ontarians of approximately $3.1 million per month. We don’t get these benefits if we ban electricity exports.

In what follows, I offer a high-level explanation for how taxing electricity exports yields these benefits.

Electricity Exports and Ontario’s Wholesale Market

When electricity is exported from Ontario to Michigan, New York and Minnesota, several things happen. First, the basic process is as follows. US importers bid into the wholesale market seeking to buy electricity while Ontario generators offer into the market for potential dispatch. Dispatch occurs at the Hourly Ontario Energy Price (HOEP) where total demand, demand from Ontario plus demand from US importers, equals marginal cost.

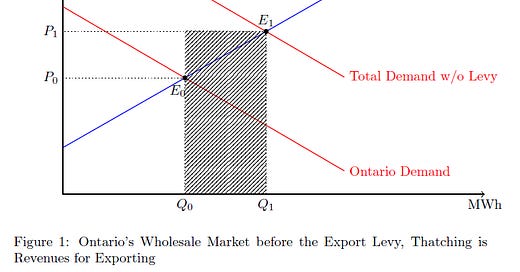

This dispatch mechanism can be seen in the following figure. The graph contains a supply curve, S, shown in blue. This supply curve reflects the merit order of marginal costs of Ontario generators. Two demand curves are illustrated in red. There is demand from the Ontario market, i.e., Ontario Demand, and Total Demand, which includes exports.

US import demand does two things. It increases the HOEP from what it would be without exports. P0 increases to P1. It also increases the volume of electricity dispatched from Q0 to Q1. Revenues earned from export equal to the shaded region.

As with all things in electricity markets, there’s more to this. In particular, almost all electricity generators in Ontario have a contract with the IESO. To keep things conceptually simple, perhaps too simple, it is useful to assume all these agreements are so-called take-or-pay contracts where generators receive a guaranteed price greater than the HOEP but are obligated to offer into the market at their marginal operating cost. (This assumption is for intuition only and isn’t necessary for the calculations below.) In other words, Ontarians commit to paying for power plants regardless of whether they generate electricity or not. This isn’t exactly how Ontario’s market works, but it’s not a bad approximation.

Because generators in Ontario are under take-ro-apy contracts, an increase or decrease to the HOEP doesn’t materially change the financial situation for Ontario consumers or generators. The HOEP simply changes how system costs are paid for. Indeed, exports can slightly improve the situation. Ontario receives revenues from US states. Some of this export revenue, goes to paying for operating costs, while some goes directly to reducing overall system costs paid for by Ontarians.

Consequences of an Export Levy in Ontario’s Hybrid Market

The obvious first consequence of an export tax is that it increases prices paid by American buyers. Because American buyers pay more, they will buy less electricity. This is reflected in the shift in the export demand curve in Figure 2. The price that Americans pay increases to PX. The change from P1 to PX is less than the full amount of the tax, because there is some elasticity to US import demand. Selling less power reduces the domestic wholesale price, the HOEP.

Fewer electrons sold to the US also means foregoing market revenue net of operating costs. Figure 2 shows the reduction in net revenues as the dotted area, an amount that equals the decrease in quantity attributable to the tax, (Q1-Q2), multiplied by the original HOEP, P1, less the cost of generating that electricity.

That’s not the end of the story, however. Taxes, unlike export bans, bring in revenue. Tax revenue is shown as the crosshatch rectangle in Figure 2. Tax revenue equals the tax rate multiplied by the new export quantity, Q2 – Q0. The benefit or loss to Ontario depends on comparing the sizes of these areas. If the crosshatch rectangle is larger than the dotted triangle, export taxes are a net win for the province.

Quantifying the Effect of an Export Taxes

Calculating the net effect of an export tax requires comparing the magnitude of foregone net revenues from the export market to the gain in tax revenues. This comparison depends on three key factors. First is the size of the tax, something under the direct control of the Government. Next is the elasticity of supply or slope of the merit order curve. The merit order reflects existing technology and the cost of generation in province. Finally, the most important factor is the elasticity of US import demand. More inelastic demand implies less foregone export revenue, and more taxes collected for any given tax rate.

Using a range of parameters, the following table shows the effect from levying export taxes on electricity shipped to the US.

Net benefits of a reciprocal 10% tariff range from a low of $250,000 to $1.8 million per month with a 10% export levy. Increasing the tax to 25% opens the possibility of up to more than $4 million in net monthly benefits for Ontario, although my instinct is that represents an upper bound. None of these gains are realized if we ban energy exports.

The code used to generate this table can be downloaded here. Estimates start from the approximate average hourly baseline in January and February of 2025, which is a HOEP of $70/MW and hourly export volume of 1545MW. The assumed elasticity of supply is 0.2 (based on this and this). Three elasticities of US import demand are used. First is a value -0.6 which I estimated using hourly export volumes and price data from IESO for 2024 and year-to-date 2025. Two older estimates are from Peerbocus and Melino (2008), who estimate a value of -0.84, and the Market Surveillance Panel (2009), who find a value of -4.55. All parameters can be changed in the code to explore different scenarios.

Based on reasonable assumptions, Ontario can be made better off in the short-run by taxing electricity exports. These gains aren’t realized with an energy export ban.

To sum up, there are four key messages:

1. Ontarians are better off with an export tax than with ban on electricity exports.

2. While there are a range of estimates, it seems likely that US electricity import demand is inelastic. This means that Ontario can earn substantial revenue from taxing exports.

3. Even if export tax revenues are used for other purposes, e.g., to support other affected industries, rather than to offset system costs, the higher electricity system costs are likely moderate. Ontario has roughly 5.5 million households. Total foregone export revenues equal $6.5 million with a 10% levy and -0.6 elasticity. So, the net domestic cost of an export tax, paid through a higher Global Adjustment, will likely be relatively minor.

4. Ideally, if a Trade War must be fought, tariffs should be levied to inflict as little harm as possible on Ontario and Canada. At the same time, we want to disrupt foreign business with the goal of convincing the US to remove their tariffs on our exports. By all accounts, placing an export levy on Ontario electricity is a good option for the province. Details matter, of course. For example, Ontario would also need to ensure power delivered to Manitoba or Quebec isn’t subsequently redirected to the US. The same goes for market leakage effects. But these details should be manageable. (We also need to hope that US states don’t ratchet up the retaliation by taxing their exports of natural gas…)